This Louisiana Wedding Anthem Is a Folklife Tradition I Am So Serious

I Be Strokin' at every wedding I've ever been to

I recently had the opportunity to chat with Louisiana’s state folklorist, and I used that time to ask her a very pressing question: Is “The Stroke” dance considered a folklore practice?

According to our state folklorists, sometimes we don’t even remember when or how we learned a tradition. Many folklife traditions are passed down through our daily interactions with those around us. Because they become a part of who we are and what we do, we often don’t remember exactly how or from whom we learned them. They are something we share with each other without any expectations other than connection.

The Louisiana Folklife Program defines folklore/folklife as the following:

Living traditions passed down over time and through space. Since most folklore is passed down through generations, it is closely connected to community history.

Shared by a group of people who have something in common—ethnicity, family, region, occupation, religion, nationality, age, gender, social class, social clubs, school, etc. Everyone belongs to various groups; therefore, everyone has folklore of some sort.

Learned informally by word of mouth, observation, and/or imitation.

Made up of conservative elements (motifs) that stay the same through many transmissions, but folklore also changes in transmission (variants). In other words, folk traditions have longevity but are dynamic and adaptable.

Usually anonymous in origin.1

As a 10-year-old, I didn’t grasp the cultural impact, but learning “The Stroke” was a core memory. Allow me to set the scene. It’s the year 2000. We’ve survived Y2K, and with a new lease on life, a group of fifth-grade girls convene at early recess. Clad in our Spice Girls paraphernalia and plaid Catholic school jumpers, we line up for our daily, self-imposed line dancing class.

On this particular day, the leader of the class had recently been introduced to the song “Strokin’” by Clarence Carter and the accompanying line dance, unofficially deemed “The Stroke,” at her cousin’s wedding. None of us were going to be made fools at the next wedding we attended by not knowing the dance. And so, we began singing in unison as we learned the words and the eight counts: “I’m strokin’ to the east, I’m strokin’ to the west, I’m strokin’ to the woman that I love the best.” Two steps to the right, one step to the left, a front ball chain, a back ball chain, three pivots and a clap.

“Srokin’” is for everybody. For years, this filthy song has brought together generations—as proven by videos of Louisiana wedding receptions. I’ve personally done “The Stroke” at almost every Louisiana wedding I’ve attended. It was non-negotiable for my own wedding playlist. Not two hours after a beautiful Catholic wedding with a full Mass, everyone from the bride’s Maw-Maw to the seven-year-old flower girl is screaming the words, “Clarence Carter, Clarence Carter, ooh shit, Clarence Carter.” Everyone has just received the Holy Sacrament of Communion. But, in my opinion, the marriage isn’t officially blessed until everyone gets on the dance floor and starts strokin’.

Why this song? I have no idea. Louisianians, as a people, are funny. I have no official source to back up this claim, and perhaps I’m biased, but it’s just the truth. So it’s no surprise that an outrageous, raunchy R&B underground hit became the unofficial anthem for our weddings. I’d love to meet the person or DJ who first decided to play it at a wedding and pay them my deepest respects.

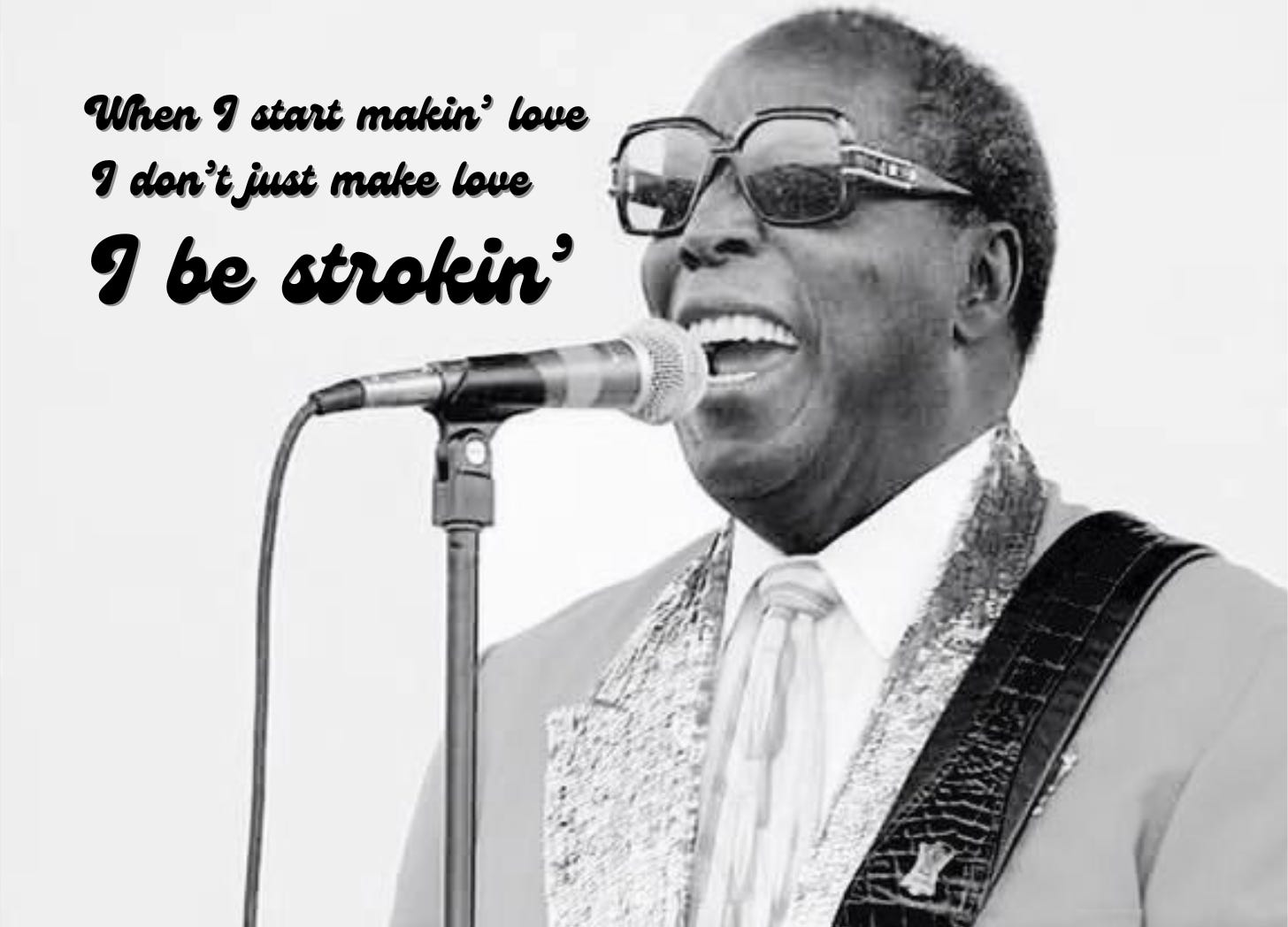

Clarence Carter is an R&B artist from Montgomery, Alabama. “Strokin’” was originally released in 1986 and was considered too dirty for radio, but that didn’t stop it from landing on the playlists of wedding DJs across the state. I don’t know if the song is a popular wedding tune in Alabama, Carter’s home state—but if anybody out there is a regular on the Alabama wedding circuit, let me know!

Fun fact: the song was also a big hit in New Zealand. It landed at #2 on the New Zealand charts and stayed on them for 46 weeks. I heard from a native New Zealander whose father was a DJ, and they shared that DJs used to play it at weddings and birthdays “because it’s a good catchy tune even though a bit uncouth.” This phenomenon proves my theory that Louisianians are somehow connected to people in every corner of the world. If there are any New Zealanders out there reading this, just know you have cousins in Louisiana—and we’ll do “The Stroke” with you anytime, anyplace.

Folklore is what ties communities together. We learn folklife practices from the people around us. Many of Louisiana’s oldest folklife traditions were meant to keep us alive or safe. Think of the architecture of our homes built off the ground to prevent flooding and the high ceilings that alleviate heat. Or consider coup de mains—work parties where communities gathered to team up on labor-intensive jobs during harvest season.2 But when you take a step back and set aside the technical lens, there’s simply the joy of gathering to do something together. And what’s more fun than dancing to a dirty song alongside your future grandmother-in-law?

To appreciate the full impact of this Louisiana wedding classic, you must have the full lyrics:

When I start making love

I don’t just make love

I be strokin’

That’s what I be doing, huh

I be strokin’

I stroke it to the east

And I stroke it to the west

And I stroke it to the woman that I love the best

I be strokin’

Let me ask you somethin’

What time of the day do you like to make love?

Have you ever made love just before breakfast?

Have you ever made love while you watched the late, late show?

Well, let me ask you this

Have you ever made love on a couch?

Well, let me ask you this

Have you ever made love on the back seat of a car?

I remember one time I made love on the back seat of a car

And the police came and shined his light on me, and I said

“I’m strokin’, that’s what I’m doing, I be stroking”

I stroke it to the east

And I stroke it to the west

And I stroke it to the woman that I love the best

I be strokin’

Let me ask you something

How long has it been since you made love, huh?

Did you make love yesterday?

Did you make love last week?

Did you make love last year?

Or maybe it might be that you planning on making love tonight

But just remember, when you start making love

You make it hard, long, soft, short

And be strokin’

I be strokin’

I stroke it to the east

And I stroke it to the west

And I stroke it to the woman that I love the best, huh

I be strokin’

Now when I start making love to my woman

I don’t stop until I know she’s sex-ified

And I can always tell when she gets sex-ified

Because when she gets sex-ifiedshe start calling my name

She’d say “Clarence Carter, Clarence Carter, Clarence Carter

Clarence Carter, ooh shit, Clarence Carter”

The other night I was strokin’ my woman

And it got so good to her, you know what she told me

Let me tell you what she told me, she said

“Stroke it Clarence Carter, but don’t stroke so fast

If my stuff ain’t tight enough, you can stick it up my’ woo!”

I be strokin’ ha! Ha! Ha! Ha!

I be strokin’

I stroke it to the east

And I stroke it to the west

And I stroke it to the woman that I love the best, huh

I be strokin’

I be strokin’ ha! Ha! Ha! Ha!

I be strokin’, yeah!

I be strokin’

I stroke it to the north

I stroke it to the south

I stroke it everywhere

I even stroke it with my, woo!

I be strokin’

I be strokin’

I be strokin’

Do you know “The Stroke?” Have you screamed “Clarence Carter ooo shit,” alongside your uncle? Let me know below!

Author’s note: The video above is footage from a wedding in New Orleans, but I grew up in the middle of the state and The Stroke was a regular thing here also. The Stroke has no cultural borders!

Louisiana Division of the Arts, “What Is Folklife and Why Study It?”, Louisiana Folklife Program, accessed November 4, 2025, https://www.louisianafolklife.org/lt/articles_essays/what_is_folklife.html.

“Cajun Folklife,” 64 Parishes, accessed November 4, 2025, https://64parishes.org/entry/cajun-folklife.